SLOP Meets: Frederic Grappe of Dynamic Vines

From a Bermondsey arch worthy of any wine soaked Bond Villain, Frederic Grappe has built one of the most important establishments in wine.

Mention the name Dynamic Vines to anyone who works in London hospitality and you’re likely to get a look of respect, a knowing nod. Even in a city where wine importers are as numerous as glasses of bad pub wine, Dynamic has established itself as one of the very best around. Fiercely low intervention and with a deep respect for wine makers, the company’s owner Frederic Grappe has spent the last two decades building one of the best portfolios in the business and helping redefine how wine is drunk and appreciated in the UK.

In a nondescript set of arches on a business park in a grey corner of Bermondsey you’re greeted by an old and squeaky metal door. Behind this industrial entry lies Dynamic Vines HQ, a breathtaking cathedral of wine. Soaring stone arches are filled with an awe inspiring quantity of bottles, the ecclesiastical dark coolness of the Victorian structure proving to be the perfect environment for wine storage. This Church’s high priest is Grappe himself, the imposing and effortlessly knowledgeable owner and founder of Dynamic.

Standing well over six feet and having not lost much of his French accent, the appropriately-named Grappe strolls happily around his vinous empire. Pause at any bottle and he can reel off anything from how their latest vintage has arrived to the name of their dog. Many of the producers at Dynamic today can be found on their first ever lists, names like Chateau Beru and Gut Oggau that have gained cult status over the lifetime of the company.

Dynamic Vines’s success did not happen overnight. Arriving in London in 1997, Grappe was one of a handful of sommeliers in a capital city where the food scene was a far cry from where it is today. “There were maybe ten sommeliers and only five good restaurants,” Grappe recalls. Fortunately, he soon found himself working in Soho opening Quo Vadis with Marco Pierre White, then at the very height of his powers. Over the next decade, Grappe rose to run the wine program across White’s restaurants before opening Michelin starred Roussillon with Alexis Gaultier and later working under Sir Terrence Conran at the Orrery.

Despite a successful career overseeing the lists of some of the top gastronomic institutions in the city, Grappe was becoming increasingly disillusioned with the wines that were on offer. “All the wines I was working with felt processed,” he explains. “It was the time when people felt they could do things better than nature.” This was a time before the term – or even the idea of – natural or low intervention wine had entered the mainstream and before even organic farming had become an accepted idea. “The reality was that there was lots of intense farming to boost quantity and then a lot of rectifying in the cellar.” Grappe found himself working with a selection of wines that had no sense of place, created to please an audience or a critic. The wines felt disingenuous. Feeling that there had to be a better way, in 2005 Grappe stepped away from restaurants to found Dynamic Vines and began to seek out the kind of wines he wanted to work with.

The wines he wanted to work with were made biodynamically, a method that was completely counter to the high yield, high intervention methodology which was the industry standard at the time. Established by philosopher Rudolph Steiner, biodynamics emphasises the interrelated qualities of farming, encouraging plant life, respecting nature and farming to the moon cycles as key principles in developing better agricultural practices. In the cellar it means low intervention, stripping away industrial yeasts and lowering the reliance on sulphur, essentially letting the expression of the terroir through the grapes be the most important element in the wine. Although that might sound quite reasonable in a world where most people are accepting of organic farming, it was quite revolutionary at the time.

SLOP NEWS

Lunch with Nino Barraco at Leo’s

On the 6th October, @leos.london on Chatsworth Road will be welcoming Nino Barraco, one of Sicily’s most celebrated winemakers for a long and relaxing lunch. Leo’s kitchen will be serving up a grand array of Sicilian specialties and Nino has dug deep into the @barracovini cellar to bring along some incredible and rare bottles.

Ticket are £50 for food excluding wine and available via Leo’s website

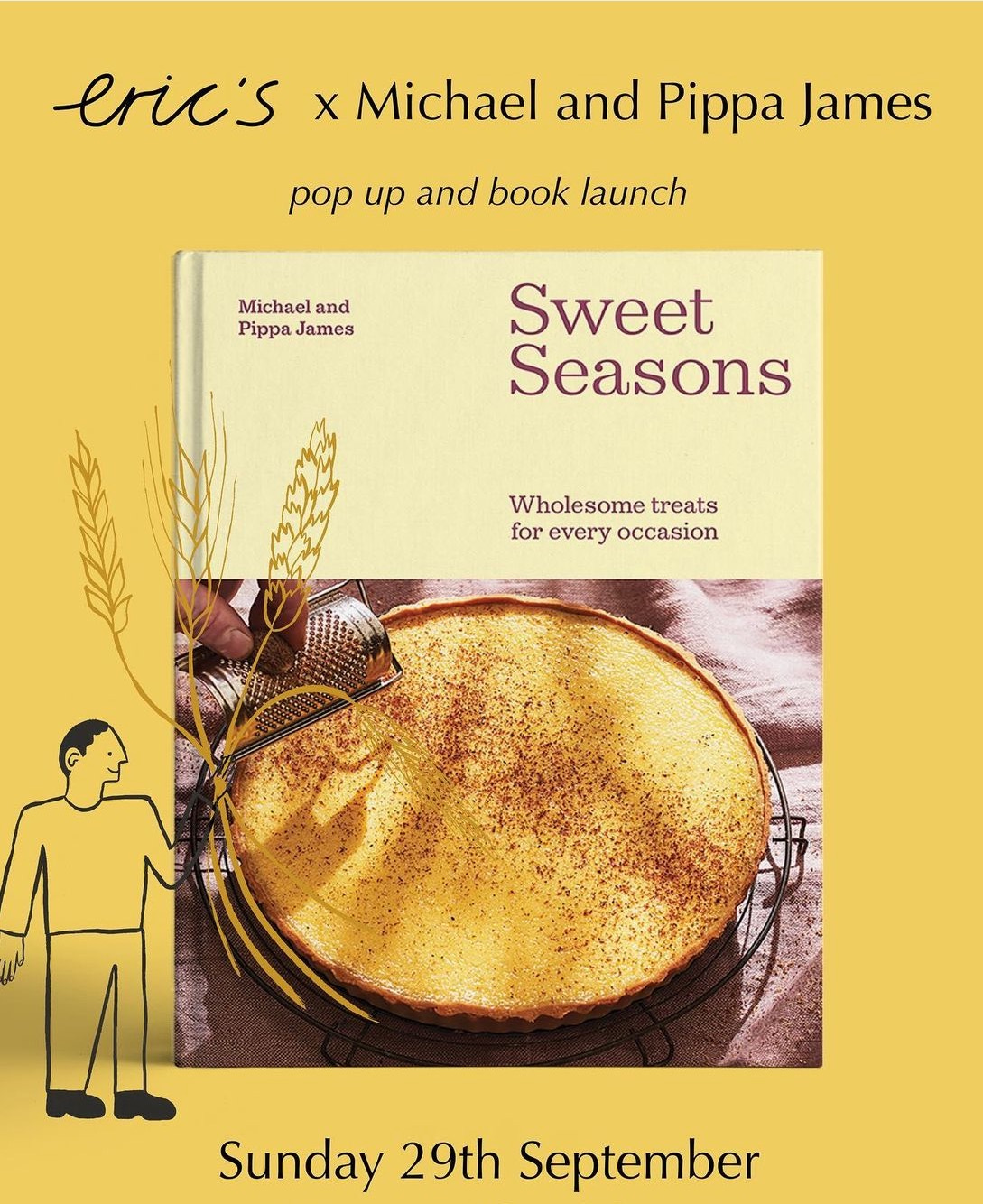

Eric’s Hosting a book launch on Sunday the 29th September

Cult East Dulwich bakery @ericslondon will be hosting the book launch of Michael and Pippa James’ third book ‘Sweet Dreams.’ Coming all the way over from Australia, the pair will also be hanging around long enough to bake a few treats from their upcoming book. Expect raspberry Wagon Wheels, pear crumble cake, apple and caramel choux buns, greengage, spelt and hazelnut linzer tarts . It’ll be a rare treat to have Eric’s open on a Sunday and one not to miss!

Dynamic Vines Continued

The London wine market and especially the established sommeliers were not always open minded about this new wave. “You take a doctor who’s been giving out antibiotics for decades and ask him to go alternative medicine, it’s not going to go well,” Grappe explains. Fortunately even if London’s lists were slow to open he had private buyers who were more interested, enthusiastic wine drinkers he had met through a decade in the industry. “They loved the wines,” he says. “They would come to me and say they couldn’t enjoy restaurant wines anymore, it was these people that kept us going for the first 24 months.”

There were also hostile reactions from some of the establishment with farming lobbies concerned with the popularisation of a farming method that requires no pesticides, fertilisers or industrial yeasts. Last year the French wine industry exceeded 11.3 billion dollars and there are many interests at play. In 2000 the wine industry in France used 3% of the agricultural land but 20% of all pesticides, with 90% of wines at french supermarkets containing pesticides as of 2013. A shift towards organic and biodynamic was a direct threat to that established way of making wine. “A lot of people didn’t want to see this so they said biodynamic was a bunch of hippies and the wines can’t age,” Grappe adds. “To this day we keep as many back vintages as we do to prove that wrong. Chateau le Puy and Emedio Pepe have a capacity to age 50, 60 years maybe more and they are made naturally.” Despite some of the negativity what was happening in the bottle was clear and people embraced this new diversity of wine.

“People here are open minded,” explains Grappe, “I met a buyer at Berry Brothers years ago and he put it like this, ‘If we ever figure out how to make wine on a different planet, I guarantee that the UK will be its first market.’”

It may not have been extra terrestrial but the prophecy turned out true and the early 2000s proved to be the beginning of an explosion of natural wine in the UK. Despite its success,Grappe bristles at the term. “I’m not a fan of [the term] ‘natural wine’ because really it doesn’t mean anything, it’s a commercial term that’s been turned into a category of wine.” Despite having become a ubiquitous phrase, ‘natural wine’ has no strict meaning; there is no inherent taste difference between a natural or conventional wine, rather it’s a difference in the principles and production.

However, there was a trend in this period towards wild, often faulty wines, the kind of thing that had led the Spectator to describe natural wine as tasting like “flawed cider or rotten sherry,” the Observer as “an acrid, grim burst of acid that makes you want to cry,” and wine critic and big red enthusiast Robert Parker to describe it as “an undefined scam”. Whilst natural wine drinkers tend to be more forgiving of slight faults like a little effervescence on opening or a hint of mousiness, these were not inherent in natural wines but rather a side effect of a rush towards new winemaking techniques.

“What’s important is the farming behind those wines.” explains Grappe of low intervention winemaking, “In 2010-2012 there was often not enough good farming behind them to make good wines. Producers would switch from conventional to so-called natural and would use no sulphite from one year to the next but they didn’t have the raw product.” Some producers realised the size of the challenge and were more cautious with Gut Oggau taking eight years to transition to zero sulphur after strengthening the ecosystem in the vineyard. As Grappe freely admits, “in the early 2010s a lot of the natural wines were all over the shop”.

In what Grappe describes as “the most multicultural wine market in the world,” tastes have continued to evolve and London has embraced low intervention and natural wines. Alongside this, the wines themselves have started to shift, often dictated by a changing climate. “The word we hear the most is ‘adapt’, this is the thing that all of the producers must focus on,” explains Grappe with some gravity. It’s not just adapting by starting to pick earlier but also adapting the style of wine. The lines between, red, rose, orange and white all starting to blur.

“We’re starting to think that we can produce wines that are much more hybrid, listening to the wines or the grapes rather than boundaries of white and red,” opines Grappe “It’s interesting why we need to put a colour into a skin contact? It’s orange for some but not others, pinot grigio for instance gives you a pink wine not orange when you introduce skin contact. The skin contact has given the chance for people to realise that different shades can happen.” At a recent tasting of Còsmic - a winemaker from Cataluña Fred describes tasting through all the wines from a lemon hued pet nat through to a deep red marselan with no real indication of where one shade ended and the other began.

In a world of increasingly inconsistent weather, it’s a change that looks permanent. Regions across the globe are having to adapt traditions of wine making that stretch back hundreds of years. “Wines from Cataluña are at 9 or 10.5% now at harvest time in July, if you wait until September, like people used to, the wines are at 16 or 16.5% and they can’t ferment. Otherwise you pick a little earlier, you use a little more skin which keeps charisma and character. You use the full potential of the grape to give that extra strength and flavour which you might not normally get at those picking dates.”

No matter what happens in the cellar, Grappe sees the weather and the terroir as the most important elements to making wine. “The vineyard is an art studio with no roof,” as he puts it. “You are always at the mercy of the weather.” Increasingly that means fighting elements that would have seemed unthinkable a generation or two ago. From wildfires in April to frost and hailstones arriving far earlier in the year than ever before, it’s the inconsistency that is hardest to fight against. “As long as vines are trained properly, heat is fine, they will go deep into the soil and get what they need. The lack of water is problematic and the accidents created by climate change, we are much more subject to the climate than we like to think we are.”

Despite the challenges, Dynamic Vines continues to thrive with natural wines being more popular than ever in a market that has started to understand the nuance of what that term may or may not mean. Grappe is satisfied, seemingly only really perturbed by the idea of running out of space in Bermondsey and the challenges his winemakers face. Next year will be the twentieth anniversary of Dynamic Vines, an occasion that will no doubt be marked with the opening of some choice cuvees. Pausing in front of a wall of one of his most prized producers, Chateau Beru, a long established producer in Burgundy that converted to biodynamic methods under the stewardship of their daughter Athenaïs “Compare Athenaïs’ Chablis now twenty years on and a conventional Chablis; it's like they’re coming from two different planets.” reflects Grappe “People have started to recognise the raw quality of the wine in those bottles.” To Grappe it looks like the proof is in the pudding, the world of natural winemaking proving itself far more adaptable to change and challenge than the conventional one.